From Forest Carbon's Project Manager, Michael O'Brien

As the effects of climate change continue to be felt across the world many nations continue to strive to meet their emissions targets by 2050. As such, each country has taken stock and is using its unique ecological, social, and financial contexts to leverage the maximum impact of any action taken.

In the UK, alongside a suite of decarbonisation programs set out in its Net Zero strategy, we have also established two of the world’s highest integrity carbon markets in the Woodland Carbon Code and Peatland Code to help privately finance this green transition.

However, the UK has more to offer, and new codes are on the horizon. Perhaps the most evocative of these is the newly emerging Hedgerow Carbon Code. It seeks to unlock the potential of these fascinating and quintessentially British examples of ecological and social infrastructure.

For those, like me, who did not grow up in a rural environment and only have a vague sense of what a hedgerow is let me direct you to ‘Natural England’s Favorable Conservation Status’ definition:

“Any boundary line of trees and/or shrubs over 20 m long and less than 5 m wide, where any gaps between the trees or shrub species are less than 20 m wide, and where native woody species form 80% or more of the cover. Any bank, wall, ditch, or tree within 2 m of the centre of the hedgerow is considered to be part of the hedgerow, as is the herbaceous vegetation within 2 m of the center of the hedgerow.”

These environments are manmade and typically heavily managed with trimming occurring on 1–3 year cycles and 20-40 year cycles of laying and coppicing (cutting back to stimulate new growth).

A (not so) quick aside into the history of hedgerows in Britain

Perhaps it is important to put hedgerows into a historical context to truly understand not only their ecological importance but also their cultural value.

Field boundaries have been present in Britain to some extent since the adoption of agriculture in the Neolithic age (~4300 BCE) and expanded rapidly during the Bronze Age (2500 – 700 BCE). It is believed that these first hedges were the remains of the ancient forest that once covered much of the British Isles.

Field boundaries and thus hedges declined in abundance after the Roman occupation of Britain ended and the Saxons succeeded them giving way to a new philosophy around land ownership and management. Land was worked communally, with a single crop field per community and the rest used as grazing. This largely continued and increased through the Norman era and the creation of landowning lordships.

In 1235 power was given to these lords to enclose areas of their land. The advent of the Tudor period (1485 -1603) allowed enclosure by force, setting into motion a series of rebellions with lords creating hedgerows and peasant revolts tearing them down.

From this time on, various bills were passed in parliament promoting and rewarding the establishment of hedgerows which peaked by 1820 and only declined when influential urbanites began to realise less, and less land was available for recreation and lobbied to stop further hedgerow expansion.

The status quo remained largely the same until the end of WW2 when food shortages inspired government-backed financial rewards for the removal of hedgerows, resulting in a 52% decrease between 1950 -2007.

This long history not only explains why hedgerows are so firmly present in our minds when we consider the British countryside but also points towards some of the ecological benefits such as old and diverse seed banks and long-established wildlife corridors. Additionally, hedgerows, can capture CO2 from the air and sequester it in the woody biomass and soils beneath.

The current situation for hedgerows is a mixed bag. The last 75 years have seen the loss of 50% of UK hedgerows with many of those that remained being mismanaged. The most recent UK condition assessment showed that in 2007 we had reached our lowest levels yet at 477,000 km, with only 48% of those being in good condition.

However, as the importance of hedgerows for carbon storage and biodiversity has been increasingly recognized across the legislature, there has been a marked change. They are now a protected habitat that covers an estimated 550,000 km (Including those that are not managed) in England alone with more on the way.

Helped by agricultural incentive schemes, the farming and rural community have risen to the challenge with 2.6 times as many hedges planted or restored through gapping up (connecting existing hedges via new planting) in 2019 to 2022 (3816.7 km) compared with 2004 to 2018 (1448.2 km), with the highest planting rate yet achieved in 2022 (1375.3 km yr−1).

Promising as this is, far more is needed to meet the UK’s ambitious targets.

Hedgerow goals in the UK

In line with the UK Government’s ambition to have British agriculture be Net Zero by 2050, and Natural England’s 335,000km hedgerow expansion target, The Committee on Climate Change has set the goal of a 40% increase in Hedgerow length by 2050; the most ambitious hedgerow target in Europe. This equates to a little over 160,000 km in England over the next 25 years, by our estimations.

Ambitious though it is, the UK farming community has backed this with The National Farmers Union, Countryside Charity, and The Organic research facility all endorsing this goal.

This focus on hedgerows is echoed in DEFRA’s 25-year environmental improvement plan which sets out the goal to create or restore 48,000 km by 2037 and a staggering 72,000 km by 2050.

To date, the modest increases we have seen have been supported by the Agricultural Incentive Scheme framework and other schemes. However, under current rates, it would take a little under 110 years to reach the target 40% hedgerow uplift. Thus, additional financing options are sorely needed.

Current financing options

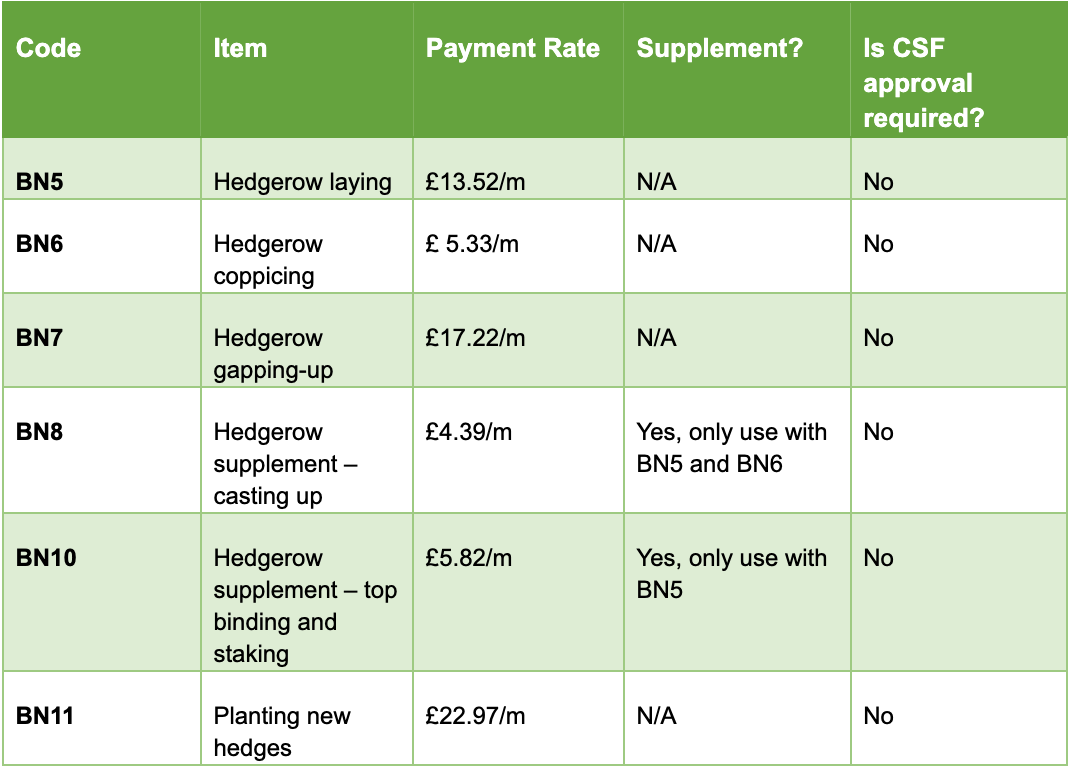

At the time of writing this article, there are several funding options available to those wanting to plant new or supplement existing hedgerows. Primarily, landowners will receive funding through The Countryside Stewardship Capital Grant (CSCG) which has been updated in 2023. See the table below for available funding under this program.

In Scotland, capital grants can be accessed through the Rural Payments and Services scheme albeit at a lower rate. Alongside these, the ‘Branching Out Fund’ provided by The Tree Council and the ‘Morehedges’ initiative provided by The Woodland Trust provide additional options for funding.

Despite these options and the raising of the CSCG’s planting grant from £11.60 to £22.97 /m, far more is needed to address landowner and farmers’ concerns: that current funding does not meet a sufficient proportion of planting costs, maintenance, and perceived losses in agricultural output. Thus, a space for the Hedgerow Carbon Code has developed.

Hedgerow Carbon Code development

Sensing an opportunity to provide a market-driven incentive to create hedgerows, a Hedgerow Carbon Code is under development. Its goal is to “unlock the environmental and income generating potential of hedgerows” by providing a matrix to calculate the carbon store held within a hedgerow based on species make-up, height, and length. This matrix would also be able to generate carbon potential for new and existing hedgerows under different management regimes.

Existing hedgerows are particularly well suited for increased carbon sequestration due to their three-dimensional structure; ‘simply doubling their height and width can quadruple their carbon storage’ says the Allerton project. These carbon gains are further added to by the heightened sequestration of soil carbon beneath older hedgerows when compared to younger ones.

The value of a carbon code such as this is vast as, much like with the Woodland and Peatland Code before it, it will incentivise renewed planting and carbon-focused management while providing a means of verifying these projects and issuing high-integrity carbon credits. Organic Farmers and Growers (who already provide auditing support for the WCC and PCC) will likely provide certification for these projects.

The benefit to land managers is just as vast, allowing them to capitalise on a resource that many arable farms already have and in doing so diversify income streams and strengthen financial resilience

The carbon and economic benefits are not all this developing code has to offer. Hedgerows are also enormously important for biodiversity. Broadly they provide food and shelter, and form wildlife corridors, for over 2000 animals and plant species in the UK. They also improve water infiltration and some even have anthelmintic properties, which are a natural dewormer for livestock.

Critically they support 82 conservation priority species, provide the most nectar of any farmland habitat, in doing so support pollination services to some crops, and are viewed as a keystone structure in promoting bird diversity.

For now, after receiving an £81.5k grant from the Natural Environment Readiness Fund (NERF) in 2021, the code is being trialled on three English arable farms, testing its accuracy and practicality. Though it is hoped that this standard will be widely available to land managers shortly, no specific timescale has yet been set. Watch this space for further updates.

Sources

- Write, J. A Natural History of the Hedgerow: and ditches, dykes, and dry stone walls: Profile Books, Chapters 2 & 3.

- Write, J. A Natural History of the Hedgerow: and ditches, dykes, and dry stone walls: Profile Books, Chapters 5 & 6. ISBN: 9781846685538

- Friar, Stephen (2004). The Sutton Companion to Local History. Sutton Publishing, pp.144-146. ISBN: 0750927232

- Blanchard, I. (1970). Population Change, Enclosure, and the Early Tudor Economy. The Economic History Review, 23(3), pp.427-445. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2594614

- People’s Trust for Endangered Species. (2021). A History of Hedgerows - People’s Trust for Endangered Species. [online] Available at: https://ptes.org/hedgerow/a-history-of-hedgerows/

- Hayward, J. Hedgerows. [online] The Tree Council. Available at: https://treecouncil.org.uk/science-and-research/hedgerows/

- Carey, P. D.; Wallis, S. M.; Emmett, B.; Maskell, L. C.; Murphy, J.; Norton, L. R.; Simpson, I. C.; Smart, S. M.. 2008 Countryside Survey: UK Headline Messages from 2007. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, p.16. (CEH Project Number: C03259)

- Natural England - Access to Evidence. Climate Change Adaptation Manual - NE751. [online] Available at: https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/5679197848862720

- Biffi, S., Chapman, P.J., Grayson, R.P. and Ziv, G. (2023). Planting hedgerows: Biomass carbon sequestration and contribution towards net-zero targets. Science of The Total Environment, [online] 892, p.164482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164482

- Staley, J T., Wolton, R., & Norton, L R. (2023). Improving and expanding hedgerows—Recommendations for a semi-natural habitat in agricultural landscapes. Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 4, e12209. https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.12209

- Biffi, S., Chapman, P.J., Grayson, R.P. and Ziv, G. (2023). Planting hedgerows: Biomass carbon sequestration and contribution towards net-zero targets. Science of The Total Environment, [online] 892, p.164482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164482

- Staley, J T., Wolton, R., & Norton, L R. (2023). Improving and expanding hedgerows—Recommendations for a semi-natural habitat in agricultural landscapes. Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 4, e12209. https://doi.org/10.1002/2688-8319.12209

/public/694/2e2/b68/6942e2b689131175280316.jpg)

/public/692/dd7/e0c/692dd7e0ca905474952387.jpg)

/public/68f/f39/36d/68ff3936defff352354004.jpg)